IAS 2020

Posted in Announcements & Events

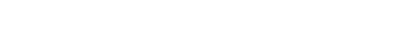

Achieving the end of AIDS and realizing UHC by 2030: what will it take?

Leveraging CIGH’s leadership in innovating thinking around the integration of global health programs, this session aims to increase the knowledge and engagement of national and global HIV policymakers, technical leads, civil society and researchers around potential opportunities for greater synergy between the HIV and UHC responses

In ratifying the sustainable development goals (SDGs), United Nations Member States have pledged to achieve a series of ambitious health and development goals. In addition to ending acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) as a public health threat, SDG3 includes a 90% reduction in tuberculosis and malaria deaths, a one-third reduction in premature deaths due to non-communicable diseases and achieving universal health coverage (UHC). UHC is the broadest of these goals, encompassing the other health-related SDGs, and is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a condition in which “all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.” UHC includes equitable access to quality essential health-care services and to safe, effective and affordable essential medicines and vaccines, and financial risk protection.

In many low- and middle-income countries, efforts to control the HIV epidemic and to achieve UHC are aligned and complementary; only by averting a growing population of citizens in need of HIV services can health systems hope to achieve universal coverage. The HIV response has also built capacity and programme infrastructure that can be used to address other health conditions. And the advantages of integrating HIV, tuberculosis, primary care and other health services are becoming increasingly clear, and benefit both those living with HIV and the broader populace. And the UHC response is also critical to the HIV response, especially in an environment in which external financing for HIV is in decline—only by establishing broad access to primary healthcare can countries sustain key elements of the HIV response for the long-term.

However, there are also areas of potential tension should either of the two responses make major decisions without regard for the other. For example, an increasingly targeted HIV response that misses potential opportunities for integration, or a UHC response that chooses not to include HIV as part of the UHC benefit package due to a perception of adequate external financing.

Investing strategically in areas of convergence between the two responses is an important strategy for ensuring greater mutual benefit and progress for both the HIV and UHC agendas.

Improving quality and patient-centeredness of care through patient, provider and community feedback

Leveraging CIGH’s innovative work with partners on patient centered public health, this session will examine challenges and opportunities of emerging methodologies for measuring patient and community experience of care, and approaches for using that information at scale for improving health outcomes.

HIV programs have been highly successful in expanding access to HIV treatment, and over 23 million people are currently on treatment worldwide. However, quality of HIV service delivery varies across sites, countries and regions, as demonstrated by marked heterogeneity in retention and mortality outcomes. Many people living with HIV, policymakers, providers and communities are neither aware of this heterogeneity, nor engaged in shaping more effective delivery systems.

WHO HIV services quality guidance outlines numerous domains of quality services, and calls for services that are effective, safe and patient-centered. These elements are related, of course, in that greater attention to patient-centeredness may result in care that is more safe and effective.

The movement for differentiated service delivery (DSD) has spearheaded efforts to make care delivery models more responsive to patient needs through changes in service intensity/frequency, provider mix, location of services, but implementers often lack data about which factors to prioritize.

To fill that gap, researchers and programs have undertaken efforts to develop a better understanding of the patient experience of care in various settings, and to understand patient’s preferences for changes in care delivery models. These data, elicited through focus groups, surveys, discrete choice experiments and other means can be fed back into care systems in a once off or continuous manner with the intent of improving outcomes. Likewise, communities themselves are being engaged to provide input on their experience with facility-level care, and to provide their ideas and hold decision-makers accountable for improving health outcomes.

Program funders such as PEPFAR and Global Fund are increasingly interested in including patient experience outcomes within routine quality improvement processes alongside conventional clinical cascade outcomes like retention and viral suppression. Yet, more must be learned before these critical new indicators can be successfully scaled.